-

Poetry Reading by Cate Marvin Inspires Students to Take Risks in Their Writing

On January 15th, the University of Detroit Mercy hosted its first Triptych Visiting Authors series reading of 2026 via Zoom. This reading featured Cate Marvin, poet and Professor of English at the College of Staten Island, City University of New York, who also teaches poetry writing in the Stonecoast M.F.A. Program at the University of…

-

If You Know Too Much of What You’re Going To Say, Then You’re Not Discovering Anything: A Virtual Poetry Reading with Joanna Fuhrman

On October 1, 2025, the University of Detroit Mercy hosted a virtual poetry reading featuring Joanna Fuhrman, poet and Assistant Teaching Professor in Creative Writing at Rutgers University. A graduate of the University of Washington’s MFA program, where she received both the Academy of American Poets Prize and the Joan Grayson Award, Fuhrman’s distinctive style…

-

UDM’s New Black Box Theatre Hosts Its First Poetry Reading with Michigan Poet Laureate Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd

On Saturday, September 27th, the University of Detroit Mercy’s newly opened Black Box Theatre hosted its first poetry reading with Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd. A writer and academic, Dr. Boyd is Michigan’s third poet laureate and currently holds the position of Distinguished Professor of African American Studies at Wayne State University. She has authored a…

-

Magnetic Poetry Contest–2025 Winners!

For the second year, UDM’s English Department sponsored a Magnetic Poetry Contest on the 2nd floor of Briggs. Students, faculty, staff, passers-by, all were invited to try their hand at original compositions using the building blocks of poetry: words on the page locker! Read the winning student poems below. ______________________ 1st Place: Ashlee Jones, “Somewhere…

-

Poet Cal Freeman Offers Reading on UDM’s Campus

Join Detroit Mercy’s Department of English as we welcome poet (and alum!) Cal Freeman to campus for a poetry reading and conversation about his latest book, The Weather of Our Names (Cornerstone Press, 2025). Books will be available for purchase. Thursday, October 23rd at 12:45 pm McNichols Campus Library, Bargman Room (2nd floor) Free and Open…

-

Poet Joanna Furhman Offers Virtual Reading!

Join University of Detroit Mercy’s Department of English as we welcome Joanna Fuhrman to a free virtual reading, hosted by UDM’s Poet-in-Residence Stacy Gnall! Open to the community: Register here. JOANNA FUHRMAN is the author of seven books of poetry, most recently Data Mind (Curbstone/Northwestern University Press, 2024) and To a New Era (Hanging Loose Press 2021). Fuhrman’s poems have…

-

Michigan Poet Laureate Melba Joyce Boyd Comes to UDM!

As part of this year’s 2025 Homecoming festivities, Michigan’s new Poet Laureate Melba Joyce Boyd will offer a poetry reading in University of Detroit Mercy’s brand new Black Box Theatre! This event is free and open to the public. An official stop on the 2025 Michigan Poet Laureate Tour, the reading is sponsored by the…

-

The 36th Annual Bauder Lecture, featuring Pulitzer Prize Winner Percival Everett

On April 25, 2025, students in Professor Stephen Pasqualina’s Winter 2025 Black Modernisms course attended the 2025 Bauder Lecture featuring author Percival Everett. Just a week before the lecture, the class concluded with intensive readings and discussions of his latest novel, James. The following is a reflection on the lecture by one of the outstanding…

-

Seeing Black Modernisms at the Detroit Institute of Arts

On March 29, 2025, Professor Stephen Pasqualina and the students in his Winter 2025 Black Modernisms course visited the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). The class came to the DIA with the intention of touring two adjacent sections of the museum: one labeled “African American,” the other labeled “Modern.” Students were to peruse these two…

-

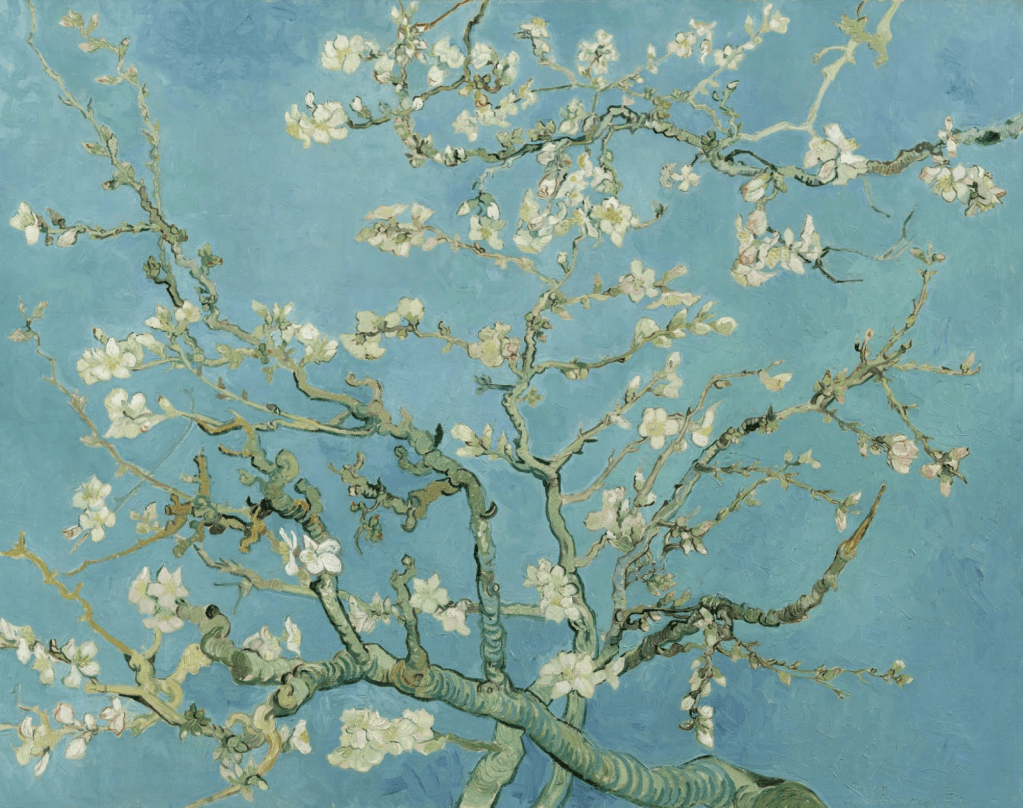

Painting with Words: Ekphrastic Poems by Detroit Mercy Student Writers

At this year’s Celebration of Scholarly Achievement and Community Engagement (CSACE), held on April 3rd 2025, University of Detroit Mercy students gathered for a reading of original ekphrastic poetry—poetry that describes, or otherwise responds to, visual art. This panel reading consisted of eight student writers—Jannath Aurfan, Maria Bitar, Emma Boucher, Alexander Comer, Asha George, Michelle…

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.